Nine people squeezed onto Mystic Moon – a record so far – in order to talk about death and dying. Our ages ranged from twenty to sixty-two, so it was a truly intergenerational event, with half the group being under thirty.

Again, I have highlighted the main discussions.

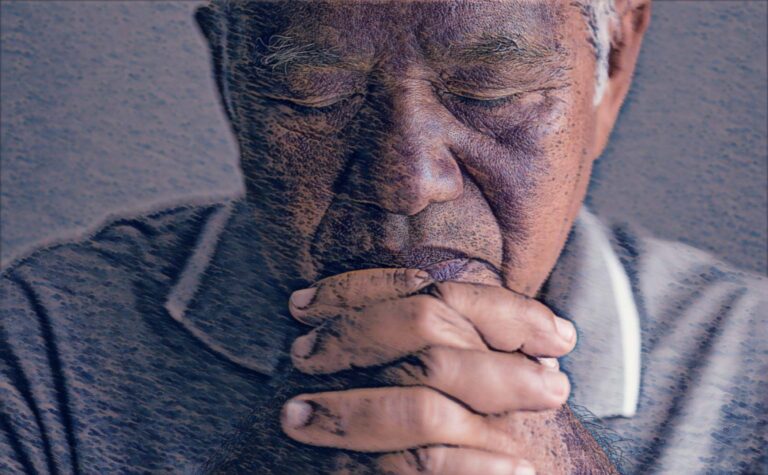

The theme that immediately arose as everyone introduced themselves was about the need to embrace death to feel fully alive. It surprised me that young people should be thinking of such things. But it quickly became apparent that these young people were very special.

One was training as a journalist, and wanted to write an article about death cafes for her university project. Another worked as a freelance journalist for a cutting edge magazine, and had received the following brief from the editor: ‘Find out what Londoners think about death.’

Wow! What a brief, and what a brave person to take it on.

Another young person worked for the prison service in drugs and rehabilitation. Her grasp on life and her own spiritual journey was astounding.

The fourth youngster possessed an equally astonishingly mature grasp on life due to a long struggle with mental health issues. The wisdom and insights that she shared with us are rare indeed.

The rest of us, being that much older, obviously had more life experience under our belts. But that’s where any differences stopped. We all expressed a profound commitment to our spiritual paths, and how this enabled us to embrace our mortality and confront our death.

‘You never know when it’s going to happen, or how it’s going to happen,’ said one young person, ‘so I focus on the present and try and get the most out of every day.’

Another young person said, ‘Knowing I am going to die makes me feel more connected to everyone. It helps me with my work too. I look at people with such broken lives and realise that most of them are sitting on huge unresolved grief and trauma. But because no-one has ever spoken to them about it, they are unconscious of how it affects them, so they end up becoming aggressive themselves, or take drugs and drink to numb the pain.’

This opened up a conversation about how death plays such an important role in self-healing.

‘All the mystic traditions and indigenous shamanic practices involve some kind of death ritual so you can be reborn,’ someone said. ‘It symbolises the death of the ego: your willingness to let go, and become who you truly are.’

But how do you let go?’ asked someone else.

‘You accept you are going to die,’ the person responded.

Someone said that in Native American and other indigenous traditions, people embrace death as a fact of life. ‘They believe that every day is a good day to die.’

We all like that!

Someone else told us about her own healing journey and how it has helped her to make the choice to die consciously. ‘When I get to the end of my life, I want to be awake and open up to whatever comes next. That is so important to me.’

“I realise this means I have continue to work on myself, and to resolve whatever is unfinished in my life. And, keep resolving things whenever they surface. It also means I have to get over any fear of death.’

This led to a discussion on how death is spoken about in our society. Several participants expressed deep concern for how death is portrayed in films and in the media. One young participant said, ‘I have learnt about death from films and television. It all seems too clean and neat. I know it’s not really like that, but I have no idea what does happen.’

Another said, ‘I think the media makes us frightened of death. It is portrayed so violently on the news and in newspapers. It’s as if everyone dies in horrible ways. And, even if someone dies naturally, it’s as if it shouldn’t have happened. That death is wrong and shocking.’

We began to talk about how this portrayal of death disconnects us from our mortality, and how it can lead to depression and spiritual anguish. ‘I believe connection is all about the spiritual journey,’ said one participant. ‘It helps you understand that there is something more than just you out there.’

‘I think it’s about being connected to the Divine,’ said someone else. ‘It’s knowing that there’s a loving force that guides me, and cares for me.’

This opened up a conversation about faith and religious belief. ‘I think it’s much harder for people who don’t have a belief. It’s much more lonely,’ said someone. ‘People need a sense of belonging to something to make them feel safe.’

(This made me think of recent research that says there are as many, if not more young people in the UK who are just as lonely as those over seventy. Assuming it is an accurate study, this is an appalling state of affairs.)

‘If only we were taught at school that death is part of our life’s experience,’ said a young person, ‘how different things would be. I think it would make us much more compassionate towards each other.’

‘We have to talk about death, and we have to confront the taboo of not talking about it,’ said another young person. ‘I want and need to talk about it. That’s why I have come here. It helps me to feel engaged and alive.’

Our death café came to a close. Although I have enjoyed and got a lot out of all the pop-ups, this one has given me much food for thought.

My voyage this summer on Mystic Moon is also a spiritual unraveling of what my aging process means to me, and how I want to spend the rest of my years until my death.

Listening to these young people so willing to embrace their mortality made me even more determined to use my time on the canals well, and to help other people to connect with what really matters to them.