I awoke yesterday morning at 5.30am to the delightful sounds of Payma’s mum gobbing up outside my bedroom window.

But my day really started when she came into my room at 6.00am to clean The Dalai Lama’s altar and light two large incense sticks.

She disappeared for a couple of minutes, to reappear with a large canister on chains full of red hot charcoal. She swung this in front of the altar several times, filling the room with smoke.

Time to make an early exit up the hill to wait for the cafe to open.

A hour or so later found me at the clinic of Dr Kumar, who is looking after a nasty cut just below my knee, the result of falling into a pothole on Sunday.

Over discussions about the physiological merits of pus and him hacking away the dead skin around my wound, our relationship has deepened – at any rate, mine has with him. He has stopped the infection from developing into septicaemia (a serious possibility) so I consider him God.

Following a good cleanout with iodine and the application of a clean dressing, I limped off to meet my two young monks and the Mongolian couple, all of whom I have grown to love dearly.

Rinchen, one of the monks, was very excited because on his way to the Tibetan café where we meet every morning for our English lesson, he had passed a film crew and was convinced that a big Bollywood movie star was about to appear.

I wasn’t going to let that go. So I suggested we could have our lesson watching what was going on.

We trooped up the street to the main Chowk (kind of square) where crowds of on-lookers had gathered to stare at a group of Indian hip-hop dancers parading in front of a cameraman.

The director, wearing a fetching trilby hat, yelled the Indian equivalent of ‘Let’s go for a take.’

Distorted music blasted from the back of a transit van and the dancers cavorted into life, forming the backdrop for a cool-looking dude complete with designer stubble and glamorous model draped over his arm.

Abandoning my students, I raced after the ensemble to watch them trying to complete their shots while the usual Indian chaos erupted about them: honking cars and lorries, swerving motorcycles, bemused cows, mangy dogs, hordes of Indians wanting to be seen on camera, and Tibetan women chanting (one can only assume in disapproval) while turning their prayer beads.

Even one of the local beggars with his awful burn scars made

an appearance, cheerfully working the crowd with his begging bowl.

I ended up snapping pictures in true paparazzi style. This caught the attention of the cool-looking dude, who gave me a great big grin.

‘Where are you from,’ he asked.

‘England,’ I said.

‘Me too,’ he replied in what I realised was a broad Brummy accent.

Well, you could have knocked me down with a feather. It turns out that this was singer Amrit Saab who hails from Birmingham and has made quite a splash on the Brit music scene. He was in the McLeod Ganj area filming a pop video for his latest single (if that’s what you call it these days).

But, by far my favourite person on set was the director’s assistant-cum-choreographer with his yellow sunglasses and red gilet. He just loved being the centre attention, and is surely destined for Bollywood.

Eventually, I rounded up my students and

took them back to the café to talk about what they had seen.

The Mongolian couple were impressed but both Rinchen and Sherab shrugged their shoulders.

Since the age of ten, these two young men have steadfastly denounced the world that Amrit Saab, and those like him, so desperately crave.

They proceeded to explain their rigorous training, which every year includes two exams on a huge range of topics such as philosophical debate (philosophy of logic), Tibetan scriptures (they have to learn it verbatim), and meditation.

I was surprised to learn that they do not actually sit in meditation until they have been studying the theory for at least twelve, and sometimes fifteen years.

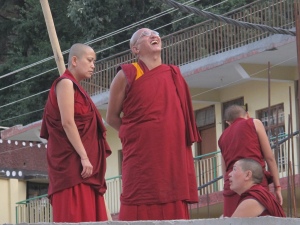

They also explained the process behind their hand-slapping philosophical debates, This takes place in pairs: one standing, the other sitting.

‘Debating is like a huge emotional release right from the heart,’ said Sherab, demonstrating the specific arm movement that accompanies all debated matters.

The right palm is held towards the earth to hold back Samsara (the continual cycle of life and death) interfering with the truth.

The left hand pulls back from the right arm as if drawing on the string of a bow. The left palm turns upwards to call on the wisdom of the Buddha, and then the palms are brought together with a mightily slap as a major point is made.

The role of the seated monk is to challenge everything the standing monk says, which means a lot of shouting, yelling and clapping. But the object is for knowledge to be shared so both monks can grow in understanding of what is true and what is false.

It takes years to perfect this debating technique. My other two monks, Charpel and Tenzin, are both well into their forties, and only received their Master certificate in debating three years ago.

We neared the end of the class, and Sherab snatched up the bill for our drinks. I was curious to know where his money came from.

He told me that monks are allowed to earn money as long as they use it for some kind of study. In this case, with the blessings of their monastery, he and Richen had earned enough money (2,300 rupees – approximately £26) to come to McLeod Ganj for two months to study English.

All their money goes towards paying for a tiny room with an outside loo, shared with another family, and for the food they eat. Before they return to their monastery, any surplus will be given away.

Sherab earns his money by teaching Thangka painting and when in serious need, also receives small amounts from his father, a Tibetan antique dealer. Rinchen earns his money by doing pujas (prayers) for people willing to pay him.

‘We are monks. We don’t need much,’ said Rinchen with a beaming smile. ‘We have one change of robes and that is all,’ (I should add that this does include a mobile phone and a computer – an essential part of life for everyone here).

I know I live in a completely different culture, but his words made me think of my bulging wardrobe back home.

I felt a little ashamed.